How Does A Heat Pump Work?

Get your pump on.

The simplest way to understand a heat pump is that it works exactly like your refrigerator, but it can run in reverse. It utilizes the principles of refrigeration to transfer thermal energy from one place to another.

The heat pump is often called the most efficient home heating and cooling technology available, achieving efficiencies far greater than 100%. But how can something generate more energy than it consumes? The answer lies not in magic, but in a sophisticated understanding of physics—specifically, the Vapor-Compression Refrigeration Cycle.

Unlike a furnace, which creates heat by burning fuel, a heat pump simply moves existing thermal energy from one location (the source) to another (the sink), a process that requires far less input energy than generation.

1. The Core Principle: The Reversed Engine

The operation of a heat pump is fundamentally an internal combustion engine operating in reverse, utilizing the Second Law of Thermodynamics. While heat flows spontaneously from hot to cold, the heat pump performs work (W) to force heat to flow from a cold reservoir (Qc) to a warm reservoir (Qh).

The total heat delivered to your home (Qh) is the sum of the heat absorbed from the environment (Qc) plus the electrical work used by the compressor (W):

This simple formula is why heat pumps are so efficient. Since the heat absorbed from the outside (Qc) is free energy, the total heat delivered (Qh) can be three to five times greater than the electrical energy consumed (W).

2. The Four Pillars of the Refrigerant Cycle

The heat pump uses a working fluid, the refrigerant, to execute four continuous state changes that move the heat. The flow is reversed by a reversing valve based on whether the thermostat calls for heating or cooling.

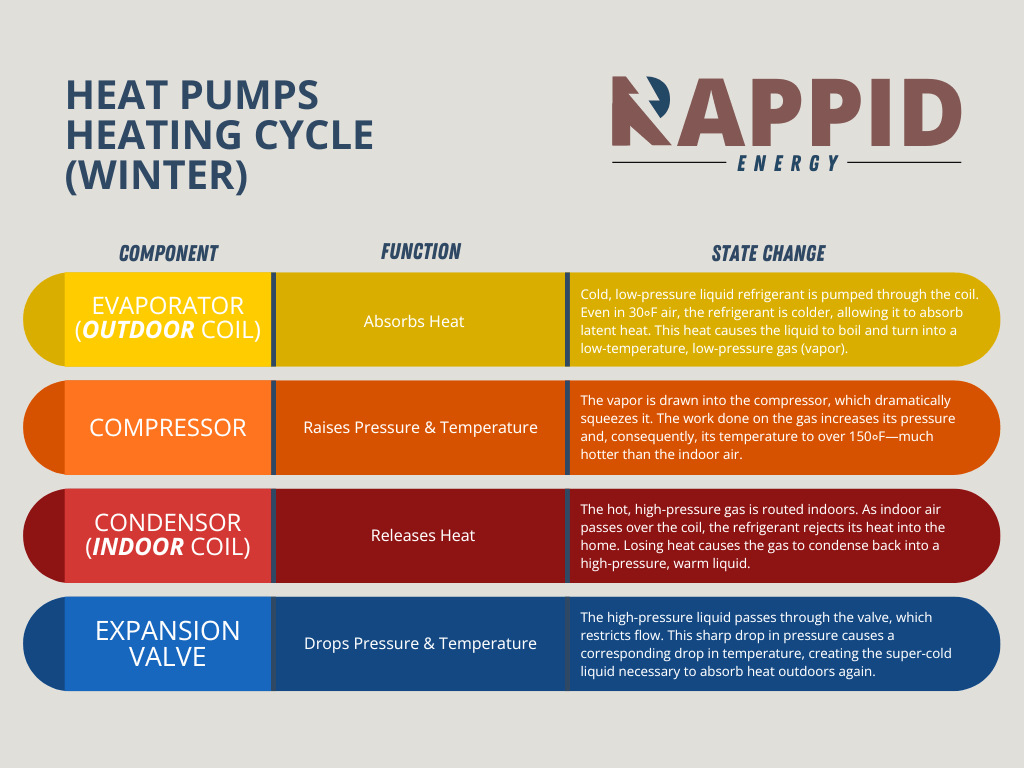

The Cycle in Heating Mode (Winter)

Even in sub-freezing air, thermal energy is hiding. Your outdoor coil acts as a heat sponge, using low-pressure refrigerant to soak up latent energy before the compressor squeezes it into high-grade warmth for your living room.

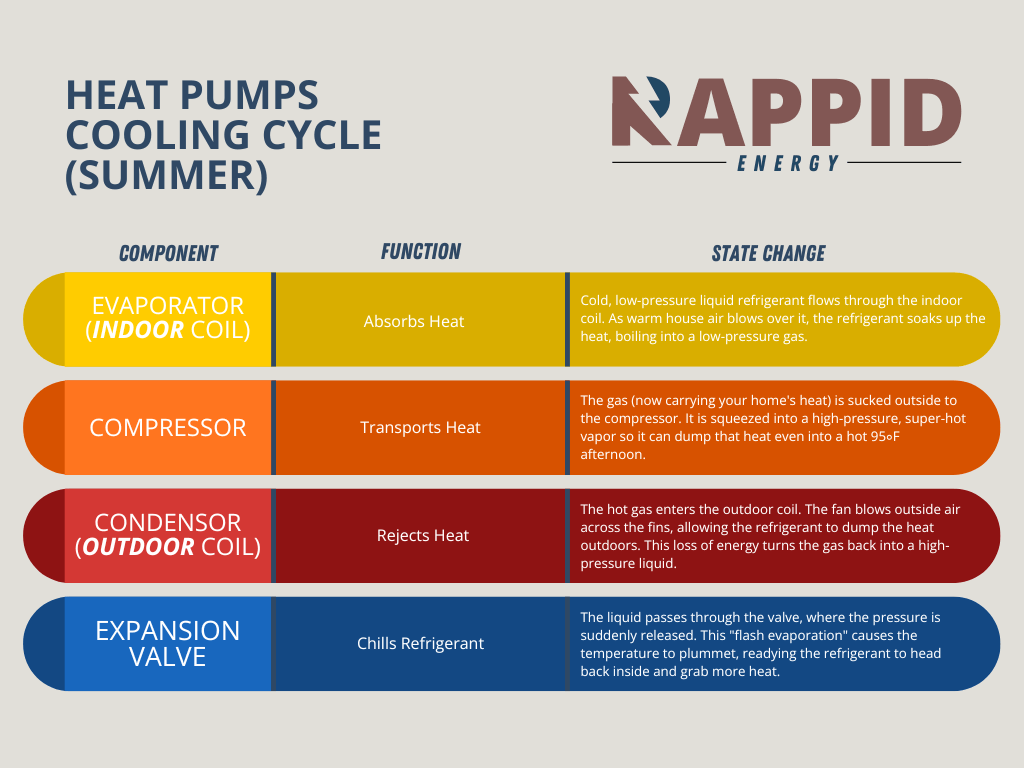

The Cycle in Cooling Mode (Summer)

Your indoor unit "steals" the heat from your living room, hitches it to a refrigerant transport, and uses the outdoor unit to dump that energy outside. By exporting the heat rather than fighting it, your home stays cool without the heavy energy lift of a traditional system.

The simplest way to understand a heat pump is that it works exactly like your refrigerator, but it can run in reverse. It utilizes the principles of refrigeration to transfer thermal energy from one place to another.

MODE: HEATING

System State: Heating Mode. High-pressure gas is sent to the Indoor Unit.

The Reversing Valve: The Key to Dual Function

The 4-way reversing valve is the signature component that differentiates a heat pump from a standard air conditioner. Controlled by the thermostat, it physically swaps the roles of the indoor and outdoor coils.

Heating Mode: It directs the hot, high-pressure gas from the compressor to the indoor coil (making it the Condenser).

Cooling Mode: It redirects the hot, high-pressure gas to the outdoor coil (making it the Condenser), and the indoor coil becomes the Evaporator.

3. Measuring True Efficiency: The Coefficient of Performance (COP)

The efficiency of a heat pump is not measured by the typical percentage used for furnaces, but by the Coefficient of Performance (COP).

The COP is a ratio:

Qh (Heating Output): The total amount of useful heat delivered into your home.

W (Work Input): The amount of electricity used by the compressor and fans to move that heat.

A standard electric resistance heater has a maximum COP of 1.0 (100% efficient).

A quality heat pump typically has a COP between 2.5 and 4.5 at mild operating temperatures, meaning it delivers 2.5 to 4.5 units of heat for every 1 unit of electricity consumed. That means for every $1 you spend on electricity, you’re "stealing" an extra $1.50 to $3.50 worth of heat from the great outdoors for free.

The Temperature Challenge

The efficiency of an Air-Source Heat Pump (ASHP) is directly affected by the temperature difference between the indoors and outdoors.

As the outside temperature drops, the heat pump must work harder to extract heat from the colder air, and the compressor must achieve a higher pressure differential.

This causes the W (work input) to increase relative to the Qc (heat absorbed), and the COP decreases. Modern "cold climate" heat pumps use advanced variable-speed (inverter) compressors and specialized refrigerants to minimize this drop, maintaining high COPs even below 0∘F.

4. Defrost Cycle and Auxiliary Heat

In very cold, damp weather, the outdoor coil (Evaporator) can drop below freezing and become frosted. Ice buildup severely restricts airflow and heat absorption. To solve this, the heat pump periodically enters a Defrost Cycle:

The reversing valve temporarily switches the heat pump into cooling mode.

The outdoor coil briefly becomes the Condenser, receiving hot gas from the compressor.

The hot gas melts the ice, which drains off as water.

During the short defrost cycle, and when the ambient temperature is too low for efficient operation, the system engages the Auxiliary Heat. This is a supplemental electric resistance coil that provides instant warmth but only operates at a COP of 1.0. Properly sized modern systems use this expensive auxiliary heat sparingly.

The Bottom Line: Better Logistics, Better Comfort.

At its core, a heat pump is the ultimate logistics manager for your home’s climate. By opting to relocate heat rather than manufacture it, you’re choosing the most efficient path physics allows. Today, comfort is about smart movement—taking the thermal energy that already exists in the environment and putting it exactly where you want it. It’s not just an appliance; it’s a more intelligent way to live.

Want to better understand how a properly-sized heat pump can help you save on bills and increase your comfort? Text us at Rappid Energy for a consultation on your home’s energy needs.